Ghost Towns in Texas - Associated with War or Native American Conflict

Texas is home to more ghost towns of any other state in the country, especially those that were established in the mid-to-late 1800s. This part of the ghost towns series focuses on the communities that either flourished or met their end because of war or Native American conflict that give a little more insight into Texas history.

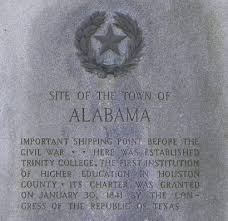

Alabama – Houston County

One of Henderson County’s most successful pre-Civil War port towns, Alabama, Texas appeared on the map in the 1830s. Due to the success of the port and expansion of the region, the Texas Congress chartered Trinity College, which operated in the town until the Civil War, serving as the first higher education institution in the county. In 1846, the town was granted a post office that served not only the town of Alabama, but a few scattered residences in the surrounding area. After the Civil War and the development of railroad systems in the region, Alabama was beginning to decline. The post office was shut down in 1878 and most of the businesses and townspeople had migrated elsewhere by 1880. Although a schoolhouse was still in operation as late as 1897, the community was almost completely dispersed just thirty years later. 1946 documented the last appearance of Alabama on maps.

Asia – Polk County

Located along U.S. Highway 287 in Polk County, two miles west of Corrigan and one hundred miles north of Houston, Asia was a small farming community that existed in the mid-1800s. Mexican War veteran James Standley developed the community in 1858 consisting of Standley’s cabinetmaking business and a few blacksmith shops. Instead of being wiped out by the Civil War, as was common among small farming communities at the time, residents of Asia built wagons and cannon carts for the Confederate Army. After the Civil War, Asia welcomed a sawmill from the Allen Lumber Company of Houston to build railroad supplies for the newly established Trinity and Sabine Railway. The sawmill brought a population boom to Asia, allowing the town to expand in 1900. However, due to deforestation, the decline of the lumber industry as a whole, and the number of mills popping up in Corrigan, Asia was abandoned by the time World War II began.

Located along U.S. Highway 287 in Polk County, two miles west of Corrigan and one hundred miles north of Houston, Asia was a small farming community that existed in the mid-1800s. Mexican War veteran James Standley developed the community in 1858 consisting of Standley’s cabinetmaking business and a few blacksmith shops. Instead of being wiped out by the Civil War, as was common among small farming communities at the time, residents of Asia built wagons and cannon carts for the Confederate Army. After the Civil War, Asia welcomed a sawmill from the Allen Lumber Company of Houston to build railroad supplies for the newly established Trinity and Sabine Railway. The sawmill brought a population boom to Asia, allowing the town to expand in 1900. However, due to deforestation, the decline of the lumber industry as a whole, and the number of mills popping up in Corrigan, Asia was abandoned by the time World War II began.

Bunker Hill – Jasper County

Bunker Hill, located in Jasper County and located on State Highway 62 just northeast of Beaumont, was named after the Massachusetts hill made famous in the Revolutionary War. Bunker Hill was one of the later ghost towns to appear on the scene, established just after 1900 when the Orange and Northwestern Railway was developed in the region in 1902 as a loading switch for the railroad. In 1910, a post office was granted to Bunker Hill, though it only lasted until 1915. The town was also home to a Western Naval Stores turpentine camp, which occupied the land until 1918 and a Texas Company (what is today Texaco) pumping station, which closed in 1943. Bunker Hill was fortunate enough to survive despite World War II economic trouble, welcoming the town’s first producing well in the oilfield in 1960. However, as more oil was found in other communities, the population of Bunker Hill began to decline. Only a few buildings and an abandoned sawmill remained by 1986. Today, the land that once made up Bunker Hill is being used as pastureland.

Fort Houston – Anderson County

At its heyday during the Republic of Texas, Fort Houston served as a blockhouse and stockade on Farm Road 1990 two miles west of Palestine in what is now Anderson County. Fort Houston was constructed on the public square of Houston in Anderson County by Captain Michael Costley’s Company of Texas Rangers, and was completed by May 19th, 1836, covering over an acre of the land. Legend has it, the blockhouse was built by rangers and the stockade was built by early settlers, and, though it was an integral point of frontier defense, it never met Native American attacks during the 1836-39 period despite attacks on nearby communities. In 1841 or 1842, Fort Houston was abandoned, and the town of Houston that was located in Anderson County was then referred to as Fort Houston. However, this community declined as well when Palestine claimed the county seat. John H. Reagan purchased 600 acres where the original Fort Houston was and the town that also claimed the name, and built his home there at the turn of the century. In 1936, the new community of Fort Houston received a State Historical Marker by the Texas Centennial Commission that marked the site of the fort and the Fort Houston Cemetery.

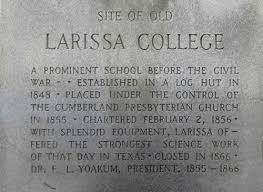

Larissa – Cherokee County

Settled by Isaac Killough and his family in 1837, Larissa was a farming community that was briefly abandoned a couple of years later when the family moved to Nacogdoches. When the Killough family returned, Native Americans had occupied the area. The Native Americans promised the settlers that they would not be harmed, but a broken treaty caused the Native Americans to revoke their promise. The Native Americans attacked the settlement, killing so many citizens that the event became known as the Killough Massacre, believed to be the largest Native American massacre in Texas history. Though resettlement efforts had been discussed after the massacre, nothing was able to be done until Texas won its statehood in 1846. Shortly after, Tennessee settlers led by Thomas H. McKee settled what would become known as the McKee Colony. The name was changed to Larissa soon after. Larissa was granted a post office in 1847 and a Masonic lodge appeared two years after. It is rumored that McKee sold a slave in Louisiana and used the profit to construct a one-room schoolhouse in the colony, which would become Larissa College when acquired by the Brazos Synod of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in 1855.Despite much success and expansion of Larissa College, the doors were closed in 1870, which started the downfall of the town, which was dependent on enrollment in the college. If that was not detrimental enough, a meningitis epidemic in 1872 put a dent in the population, followed by the development of the Kansas and Gulf Shore Line Railroad that went through the town just ten years later. In the late 1880s, though, some African American families moved to Larissa and kept it alive through the Great Depression. However, as time went on, residents of Larissa moved away, leaving only a few scattered houses by 1990.

Settled by Isaac Killough and his family in 1837, Larissa was a farming community that was briefly abandoned a couple of years later when the family moved to Nacogdoches. When the Killough family returned, Native Americans had occupied the area. The Native Americans promised the settlers that they would not be harmed, but a broken treaty caused the Native Americans to revoke their promise. The Native Americans attacked the settlement, killing so many citizens that the event became known as the Killough Massacre, believed to be the largest Native American massacre in Texas history. Though resettlement efforts had been discussed after the massacre, nothing was able to be done until Texas won its statehood in 1846. Shortly after, Tennessee settlers led by Thomas H. McKee settled what would become known as the McKee Colony. The name was changed to Larissa soon after. Larissa was granted a post office in 1847 and a Masonic lodge appeared two years after. It is rumored that McKee sold a slave in Louisiana and used the profit to construct a one-room schoolhouse in the colony, which would become Larissa College when acquired by the Brazos Synod of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in 1855.Despite much success and expansion of Larissa College, the doors were closed in 1870, which started the downfall of the town, which was dependent on enrollment in the college. If that was not detrimental enough, a meningitis epidemic in 1872 put a dent in the population, followed by the development of the Kansas and Gulf Shore Line Railroad that went through the town just ten years later. In the late 1880s, though, some African American families moved to Larissa and kept it alive through the Great Depression. However, as time went on, residents of Larissa moved away, leaving only a few scattered houses by 1990.

Linville – Victoria County

New Port was home to John J. Linn, who owned warehouses in the community, which was an important entry port in the 1830s. As the community grew, the population rose to 200 by 1839, and the name was changed to Linville after its founder. Just as Larissa was subject to Native American raids, Linville was a victim of raids from the Comanche tribe on August 18th, 1840. The Comanche raid was a result of the Council House Fight in San Antonio in March of 1840, when the Penateka Comanche chiefs were killed. The raid caused residents of Linville to flee to the nearby bay to escape the attack while the Comanche tribe looted warehouses and homes in the area before continuing on their way. Meanwhile, the Texas Militia had formed and met the Comanche tribe at Plum Creek, which is located near downtown Lockhart. This is where the famed Battle of Plum Creek took place, effectively extinguishing Comanche raids on settlements. In 1936, a historical marker was granted to the town commemorating the “Last Raid” of the Comanche tribe.

Haley is a senior at Stephen F. Austin State University, majoring in English and minoring in Spanish and Linguistics. After graduation, she hopes to go to graduate school for a Master’s in English and become an editor.