Nacogdoches Census Report Project

Censuses from the Spanish colonial period are an invaluable source for answering geographical, genealogical, and sociological questions about early multi-ethnic populations in Texas. We chose to distribute information based on these censuses here in order to provide greater access to understanding how Nacogdoches, one of the oldest towns in Texas, was established and grew. The population shifts happening at the time in the region can be tracked especially by the birthplace of the residents who migrated to the area following the closing of a nearby Spanish outpost. Additionally, the social and economic distribution of the populace is present in the Nacogdoches censuses under data for caste and occupation.

The censuses conducted in Texas reflect the drastic population shifts happening in the region. The closing of presidios, Comanche raids, and social tensions between mission settlers and populations from the Canary Islands, motivated the abandonment of some settlements and the rapid expansion of others. No longer feeling threatened by the French, a band of residents moved into Nacogdoches, the site of a mission established for the local Caddos in 1716. The town of Nacogdoches itself had an established non-missionary population by 1772, the year Spain closed a settlement in Los Adaes, Louisiana and forced its residents to resettle elsewhere, primarily in San Antonio. The three-month journey from the former Los Adaes settlement to San Antonio was one from which many migrants died attempting. There was an incentive, therefore, to relocate in the smaller, easternmost community of Nacogdoches.

The first formal censuses conducted for Spain emerged during the reign of Carlos III, who ordered them to be completed throughout the empire starting in 1768 when the first comprehensive report was compiled for mainland Spain. Because of this demand for documentation, administrative officials would sometimes repeat information in records for multiple villages. In the New World censuses were often submitted by the local priest or mayor on a less comprehensive scale, representing a particular town or region of interest. For example, the first census in Texas was conducted in 1777 and focused only on the expanding population of San Antonio. Census collection in Nacogdoches was further delayed until 1792 and continued every year thereafter.

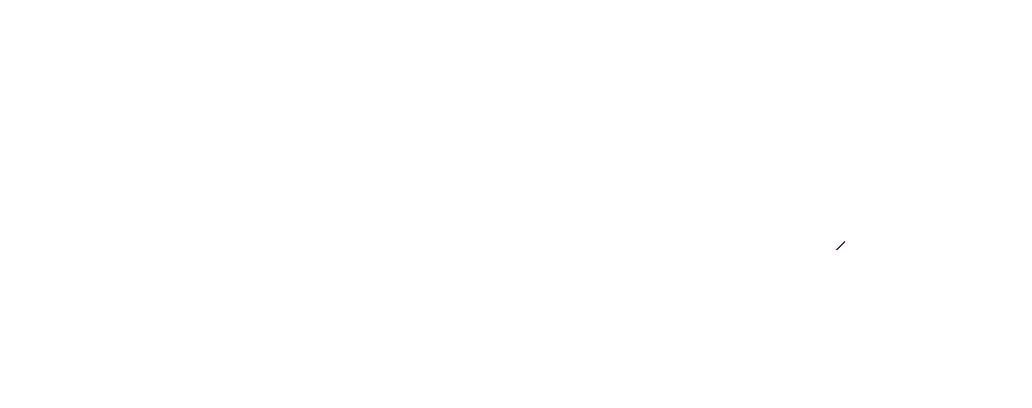

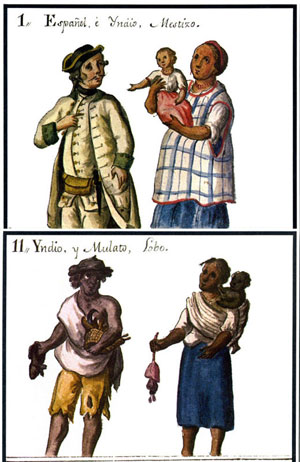

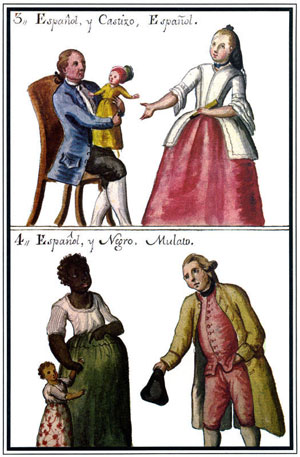

Initially, racial distinctions in New Spain were based solely on the recognition of three categories, Spanish, black, and Indian. In response to increasing inter-marriage among colonists, however, Spain expanded these categories into a more complex racial caste system that included numerous socially ranked racial labels. Because of the economic and political privileges allotted to members with a higher ranking status, efforts to illegally change rank occurred throughout New Spain. By the mid 18th century, the races had so intermingled that racial status was increasingly determined by cultural and social considerations, a change that rendered the system a less relevant reflection of race itself.

The main castes represented in New Spain are: Spanish, Mestizo, Mulatto, Coyote, Lobo, Indian, African, and Slave. The Spanish caste was further divided into Criollos, or Spaniards born in the Americas, and Peninsulares, or Spaniards born in Spain. The designation of “Guachipine” was a more general term for European-born citizenry. Most Guachipines who were not Spaniards sought to become legally Spanish when they adopted the local and language and customs. Criollos received all the same privileges as Guachipines but were not allowed to occupy the highest-ranking positions in the church or government. At one point, Criollo women and their families sought to marry them to Guachipine men, creating a shortage of women for Criollo men. As a result, greater intermarriage was encouraged between Criollo men and women of lower castes. As in other caste systems, the rights of its members were allocated according to rank, further creating a culture of caste defiance both legally and socially. The mixed-blood castes of Mestizo, Mulato, Coyote, Lobo or “wolf”, Castizo, and Salta Atras or “skip back” retained all the same rights of Criollo minors except on the topic of political involvement. They were not allowed access to high-level military, religious, and political positions. Indians and Blacks had the same rights as mixed-bloods but were forced to pay an additional annual tax to the Spanish crown. Those who failed to pay were arrested and often imprisoned.

This disparity in privileges among the castes motivated efforts to change castes and inconsistencies in the system led to its defiance in Texas. Caste assignments didn’t always reflect the person’s caste according to the rules and definitions. The local priest was entrusted with the judgment of a person’s caste at the time of baptism. The initial procedures for arriving at this decision were later manipulated to reflect a family’s wealth and cultural affiliations. In many communities where Indians adopted Spanish religion, customs, and language, the parish priests no longer baptized them as Indians. Throughout New Spain, inhabitants also sometimes paid for illegal documents reflecting a different caste assignment. Because of the remote location of the northernmost region that includes New Mexico and Texas, this activity was more frequent than in other parts of the empire. For these reasons, statistics on the caste system presented here is not a precise measurement of ethnic origin. On the other hand, the censuses still provide a general idea of the origin and background of the population and offer valuable insight into the social and economic distribution of early Nacogdoche

The primary census documents were transcribed by CRHR research associates Dr. Matthew Babcock and Meagan Cockram are based on photocopies of originals that come from the Bexar Archives, a collection of presidio documents pertaining to San Antonio de Bexar. These originals are housed at the Briscoe Center of American History at the University of Texas at Austin and microfilm copies are available at the Ralph W. Steen Library at Stephen F. Austin State University. Translations of the original documents that are included here but were not completed by CRHR are based on copies of those completed by Robert Bruce Blake (1877-1955). Blake was a county clerk and court reporter in Jasper, Texas who spent much of his life translating and transcribing Spanish documents pertaining to the history of the region. The current transcriptions and future translations provided by CRHR are based on the documents in the SFA microfilm rolls and original documents not already translated by Blake.

The present and future plans for the census project at CRHR include gathering statistical demographic and qualitative data on the area at the time and assembling that information into a Geographic Information System (GIS) map. We will continue to compile statistics and gather relevant information pertaining to the censuses from 1792 until 1836, the year the Texas Republic declared its independence. We are drawing from a number of sources, from primary documents to secondary census analyses. Although census documents themselves have been available to the public for years, CRHR’s mission is to provide a bundled source of data that would support and foster further research of the East Texas region prior to 1836. A GIS format would allow visitors to view and make observations about the data using one of the most state-of-the-art research tools available. Developing this stage of the project will involve collaboration with GIS graduate students from the SFA campus. The end result will be a GIS map available to all scholars on the CRHR website.

The long-term objective of the census project at CRHR is to assemble the statistical, demographic, and qualitative data from Nacogdoches censuses from 1792 to 1836 into a Geographic Information System (GIS) map. Although census documents themselves have been available to the public for years, this project will provide a more accessible bundled source of data to support and foster further research of the East Texas region prior to 1836. A GIS format would allow visitors to view and make observations about the data using one of the most state-of-the-art research tools available. Developing this stage of the project will involve collaboration with GIS graduate students from the SFA campus. The end result will be a GIS map available to all scholars on the CRHR website.

The first formal censuses conducted for Spain emerged during the reign of Carlos III, who ordered them to be completed throughout the empire starting in 1768 when the first comprehensive report was compiled for mainland Spain. Because of this demand for documentation, administrative officials would sometimes repeat information in records for multiple villages. In the New World censuses were often submitted by the local priest or mayor on a less comprehensive scale, representing a particular town or region of interest. For example, the first census in Texas was conducted in 1777 and focused only on the expanding population of San Antonio. Although Nacogdoches was founded in 1779, the first census was not conducted until 1792 and continued only sporadically thereafter.

Initially, racial distinctions in New Spain were based solely on the recognition of three categories, Spanish, black, and Indian. In response to increasing inter-marriage among colonists, however, Spain expanded these categories into a more complex racial caste system that included numerous socially ranked racial labels. Because of the economic and political privileges allotted to members with a higher ranking status, efforts to illegally change rank occurred throughout New Spain. By the mid 18th century, interracial mixing was so prevalent that it was increasingly determined by cultural and social considerations, a change that rendered the system a less relevant reflection of race itself.

The main castes represented in New Spain were: Spanish, Mestizo, Mulatto, Coyote, Lobo, Indian, African, and Slave. The Spanish caste was further divided into Criollos, or Spaniards born in the Americas, and Peninsulares, or Spaniards born in Spain. The designation of “Guachipine” was a more general term for European-born citizenry. Most Guachipines who were not Spaniards sought to become legally Spanish when they adopted the local and language and customs. Criollos received all the same privileges as Guachipines but were not allowed to occupy the highest-ranking positions in the church or government. At one point, Criollo families sought to marry their daughters to Guachipine men, creating a shortage of Criollo women available for Criollo men. As a result, greater intermarriage was encouraged between Criollo men and women of lower castes.

As in other caste systems, the rights of its members were allocated according to rank, further creating a culture of caste defiance both legally and socially. The mixed-blood castes of Mestizo, Mulatto, Coyote, Lobo or “wolf”, Castizo, and Salta Atras or “skip back” retained all the same rights of Criollo minors except on the topic of political involvement. They were not allowed access to high-level military, religious, and political positions. Indians and Africans had the same rights as mixed-bloods but were forced to pay an additional annual tax to the Spanish crown. Those who failed to pay were arrested and often imprisoned.

This disparity in privileges among the castes motivated efforts to change castes and inconsistencies in the system led to its defiance in Texas. Caste assignments didn’t always reflect the person’s caste according to the rules and definitions. The local priest was entrusted with the judgment of a person’s caste at the time of baptism. The initial procedures for arriving at this decision were later manipulated to reflect a family’s wealth and cultural affiliations. In many communities where Indians adopted Spanish religion, customs, and language, the parish priests no longer baptized them as Indians.

Throughout New Spain, inhabitants also sometimes paid for illegal documents reflecting a different caste assignment. Because of the remote location of the northernmost region that includes New Mexico and Texas, this activity was more frequent than in other parts of the empire. For these reasons, statistics on the caste system presented here are not a precise measurement of ethnic origin. On the other hand, the censuses still provide a general idea of the origin and background of the population and offer valuable insight into the social and economic distribution of early Nacogdoches.

The primary census documents were transcribed by CRHR Research Associate Matthew Babcock. Ph.D. and Research Assistant Meagan Cockram, M.A. and are based on microfilm copies from the Bexar Archives housed at the Ralph W. Steen Library at Stephen F. Austin State University. The original manuscript collection, from the presidio of San Antonio de Bexar (1729-1836), is housed at the Briscoe Center of American History at the University of Texas at Austin. The translations included here are photocopies from Volumes XVIII and XIX of the R.B. Blake Collection. Robert Bruce Blake (1877-1955) was a county clerk and court reporter in Jasper, Texas who spent much of his life translating and transcribing Spanish documents pertaining to the history of the region.

Bexar Archives, microfilm. Ralph W. Steen Library, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX.

R.B. Blake Collection, transcripts and translations. Ralph W. Steen Library, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX.

Chipman, Donald E. Spanish Texas, 1519-1821. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.

Platt, Lyman D. Census Records for Latin America and the Hispanic United States. Baltimore, MD; Genealogical Publishing Company, 1998.

Tjarks, Alicia V. “Comparative Demographic Analysis of Texas, 1777-1793” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 77 (January 1974): 291-338.

University of Texas Institute of Texan Cultures. Residents of Texas, 1782-1836. 3 vols. Nacogdoches, TX: Ericson Books, 1984-1996.