East Texas Ghost Towns Series - Destroyed by Natural Disasters

East Texas is full of ghost towns that give little snapshots of Texas history. Some of these hidden gems have quite an unusual story that set them apart from other “typical” ghost towns. This article focuses on the towns that met their end due to some kind of natural disaster, ranging from tornadoes to raging fires.

Munz – Cass County

Like many small Texas towns in the late 1880s, Munz  was originally settled to be a lumber town. Texarkana natives and brothers Harry and Gus Munzheimer saw an opportunity to establish a branch of their lumber company in Cass County north of State Highway 77 and east of FM 994. They chose the name of Munz to save people the trouble of trying to pronounce Munzheimer. At first, the town was pretty successful; a post office was granted in 1905 with postmaster Edgar W. King, a hotel, train depot for the Northeast Texas Railroad Company, a boarding house, and a brickyard were constructed to support the mill. When the Northeast Texas Railroad Company’s railroad was finished, the Woodmen of the World, an organization that aims to benefit communities, threw a picnic at Sulphur Springs that was attended by nearly 2,000 people. Munz met its end on March 31st, 1914, when a tornado completely demolished the community. Despite efforts to rebuild the town, the city of Munz was abandoned within a year of the tornado. There are still remnants of the train tracks in the town that can be seen today, which serve as the only physical reminder of Cass County’s lost lumber community.

was originally settled to be a lumber town. Texarkana natives and brothers Harry and Gus Munzheimer saw an opportunity to establish a branch of their lumber company in Cass County north of State Highway 77 and east of FM 994. They chose the name of Munz to save people the trouble of trying to pronounce Munzheimer. At first, the town was pretty successful; a post office was granted in 1905 with postmaster Edgar W. King, a hotel, train depot for the Northeast Texas Railroad Company, a boarding house, and a brickyard were constructed to support the mill. When the Northeast Texas Railroad Company’s railroad was finished, the Woodmen of the World, an organization that aims to benefit communities, threw a picnic at Sulphur Springs that was attended by nearly 2,000 people. Munz met its end on March 31st, 1914, when a tornado completely demolished the community. Despite efforts to rebuild the town, the city of Munz was abandoned within a year of the tornado. There are still remnants of the train tracks in the town that can be seen today, which serve as the only physical reminder of Cass County’s lost lumber community.

Zana – San Augustine County

Similar to Munz, Zana was established in the late 1880s. One of the first towns in San Augustine County, Zana was originally intended to be a sawmill community, although the mill would take a while to be successful. Zana was granted a post office in 1886, and just ten years later, the population had risen to fifty. In 1896, the community had Baptist churches, a gritsmill, a cotton gin, and two livestock ranches. By 1914, an improved sawmill and general store had opened. However, the closing of the post office in 1916 was the first step toward the end of Zana. In ten years’ time, there were only a few scattered residencies and the town no longer appeared on highway maps. Zana’s story does not stop there – the 1960s is when the remnants of Zana were completely washed away by the Sam Rayburn Reservoir, destroying all evidence of the quaint sawmill town once and for all.

Indianola – Calhoun County

Indianola has a rich war history, but its demise landed it on the natural disasters list. Originally established in 1846 under the name Indian Point, the town was a landing place for German immigrants, who built the first residences in the area. During the Mexican War, Indian Point was a deep-water port whose army depot supplied military materials to the Texas army. In 1847, the town was granted a post office and by January of the following year, stagecoach service was established in the town. In February of 1849, the town’s name was officially changed to Indianola, and the newly named community served as the county seat for Calhoun County from 1852-86. The town was so successful that it became one of Texas’ largest ports – so large, in fact, that it was the primary port for American and European immigrants to travel into Texas for a time. Additionally, it was on the eastern end of the southern Chihuahua Trail, a military road that led to San Antonio, Austin, and Chihuahua, Mexico. It was also a stop along the shortest overland trail to the Pacific coast. Indianola had multiple newspapers, the first being the Bulletin, followed by the Courier, the Times, and the Indianolan. During the Civil War, the town was raided and looted by Union forces twice, finally ending the Union’s occupation in 1864. When the Civil War ended, Indianola found another way to make history, Indianola was the first town in the world that shipped mechanically refrigerated beef from their port, thereby revolutionizing the method by which to transport refrigerated food. Unfortunately, a hurricane nearly annihilated the town on August 20th, 1886, but the fires from the storm’s aftermath inflicted fatal damage. By 1887, nothing was left of the once booming port town.

New Birmingham – Cherokee County

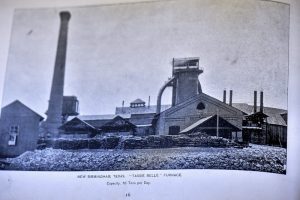

Formerly known as the “Iron Queen of the Southwest,” New Birmingham was once one of the most prominent towns in the Texas iron ore industry. In the mid-1880s, sewing machine salesman Anderson B. Blevins moved to East Texas from Alabama and envisioned an iron ore town akin to the Birmingham of his home state after seeing the iron ore depository already in operation at the Rusk Penitentiary. Blevins recruited prominent businessmen from Alabama, including James A. Mahoney, Robert Van Wych, and William Harrison Hamman, and founded the Cherokee Land and Iron Company in 1888. The following year, the company was named the New Birmingham Iron and Land Company and  operated a fifty-ton blast furnace, named Tassie Bell after Blevins’ wife. New Birmingham was along the Kansas and Gulf Shore Line Railroad, and the founders planned to create a whole community, including the three-story Southern Hotel. The Southern Hotel which was the talk of the town due to its brickwork, electric lights, running water, and upscale restaurant. The hotel also served guests such as President Grover Cleveland, Governor James Stephen Hogg, and railway tycoon Jay Gould. Although New Birmingham was successful in its heyday, trouble began brewing during the early 1890s with the Alien Land Law, which prohibited foreign parties from owning land in Texas. The law threw a wrench in the deals Blevins wanted to make with a pair of English businessmen to expand the New Birmingham Iron and Land Company. The next domino that fell for New Birmingham was when Willian Harrison Hammon was murdered by a local businessman who thought Hammon insulted his wife in July 1890. Reportedly, Hamman’s wife ran through the town and cursed it, pleading God to “leave no stick or stone standing.” Finally, on July 4th, 1893, the Cherokee County Banner, a local newspaper, reported that there was an explosion of the furnace Tassie Bell, destroying the business and putting many people out of work. Despite efforts to rebuild the town, the businesses never recovered, bringing the end of New Birmingham for good. There is a historical marker at the site, along with ruins of the furnace at Tassie Belle Park that mark where the “Iron Queen of the Southwest once stood.”

operated a fifty-ton blast furnace, named Tassie Bell after Blevins’ wife. New Birmingham was along the Kansas and Gulf Shore Line Railroad, and the founders planned to create a whole community, including the three-story Southern Hotel. The Southern Hotel which was the talk of the town due to its brickwork, electric lights, running water, and upscale restaurant. The hotel also served guests such as President Grover Cleveland, Governor James Stephen Hogg, and railway tycoon Jay Gould. Although New Birmingham was successful in its heyday, trouble began brewing during the early 1890s with the Alien Land Law, which prohibited foreign parties from owning land in Texas. The law threw a wrench in the deals Blevins wanted to make with a pair of English businessmen to expand the New Birmingham Iron and Land Company. The next domino that fell for New Birmingham was when Willian Harrison Hammon was murdered by a local businessman who thought Hammon insulted his wife in July 1890. Reportedly, Hamman’s wife ran through the town and cursed it, pleading God to “leave no stick or stone standing.” Finally, on July 4th, 1893, the Cherokee County Banner, a local newspaper, reported that there was an explosion of the furnace Tassie Bell, destroying the business and putting many people out of work. Despite efforts to rebuild the town, the businesses never recovered, bringing the end of New Birmingham for good. There is a historical marker at the site, along with ruins of the furnace at Tassie Belle Park that mark where the “Iron Queen of the Southwest once stood.”

Haley is a senior at Stephen F. Austin State University, majoring in English and minoring in Spanish and Linguistics. After graduation, she hopes to go to graduate school for a Master’s in English and become an editor.